- Home

- Kim Addonizio

The Palace of Illusions Page 2

The Palace of Illusions Read online

Page 2

But what if Grandpa is there, too, with his oxygen tank, wetting his pants? Annabelle looks around the church. She needs to get the Holy Spirit right away. But all she sees are the pews filled with people, and light through the stained glass windows above them, and Jesus hanging on the big cross in his diaper, looking like he is asleep.

After church they go to Sue’s Kitchen for lunch. Annabelle is wearing her pink dotted Swiss dress and Communion shoes, and her mother is dressed up and has used rollers in her hair so it has waves in it. Her mother orders Salisbury steak and gravy. Annabelle gets fried chicken and is allowed to have lime Jello for dessert. She drinks her milk with a straw, blowing pale white bubbles into the glass.

“What a sweet little angel,” someone says.

Annabelle looks up. A man is standing next to their booth, a big pink-cheeked man with a neat black beard and no hair on his head. He has large, fleshy lips that make her think of the wax ones the Walmart sells at Halloween.

“She sure is a beauty,” the man says, but he is looking at her mother, not Annabelle. He leans both hands on their table, meaty hands with big hairy knuckles and long fingers and—she counts them quickly—six rings.

“Sweet!” her mother says. “Stubborn as a mule, is what she is.”

Annabelle is surprised by how her mother says it; her voice is soft as a melted butter pat.

“Her mother ain’t bad, neither,” the man says. His voice is a butter knife, slipping in easily, smearing the butter around on soft bread.

Annabelle slides down the back of the leather booth until her feet are way under the table and her head is on the seat, and squinches her eyes shut.

“You raising her alone?” the man says.

“With God’s help.”

This is the first Annabelle has heard about God helping out.

“I can’t say I’m a believer, myself,” the man says, “though sometimes I figure there must be something else out there. I mean, all that space, there’s got to be, right? Even if it’s only little green men with bug eyes.”

Annabelle’s mother laughs, and Annabelle pictures green men the size of ants, crawling out of an anthill.

“I envy those who have faith,” the man says.

“Well, to each his own,” her mother says. “I believe everyone should get along.”

“I wouldn’t mind getting along with you,” the man says, and Annabelle thinks about the green man-ants swarming up the ramp into Grandpa’s trailer, crawling along his wheelchair and into his eyes and nose and ears, starting to eat him alive.

The man stands there talking to her mother for what seems like forever.

“I have to pee,” Annabelle says. Her mother just waves her hand, so Annabelle goes by herself. When she comes out, the man is gone. She follows her mother out to their van.

“He’s going to come by the motel,” her mother says. “He usually stays at the Days Inn, but they don’t have free HBO like we do, and all they serve for breakfast are bad donuts, and we have those cinnamon buns from Sue’s. Do you want one tomorrow? You can have one tomorrow.” Her mother babbles on, the way she did when she was taking those green and white pills to help her stop eating. They didn’t work; she just ate and talked all day and cried harder at night.

When they get to the motel her mother goes back to work in the dress she wore to church, instead of changing into sweatpants and a T-shirt like she usually does, and Annabelle leans forward on the couch looking at Sam in his cage, poking her finger in to touch him.

The man comes that night, through the door at the back of the office and into their apartment. Annabelle spies on them from her bedroom, her door cracked open. They are on the couch together, laughing. The man has on a T-shirt, thick dark hair all down his fat arms. One dark, ugly arm is around her mother’s shoulders. Her mother lets her head fall back, and the man pours beer from the bottle into her mouth.

“Atta girl,” he says. “Shit, you can hold it.”

Her mother sits up, reaches for a bottle on the table. There are a lot of bottles. Her mother’s legs are open, her dress hiked up. Annabelle watches the man put his own beer on the floor, watches his hand disappear under her mother’s dress. Her mother squirms, then pulls his hand away.

“Not here,” she says. “My kid—”

“She’s asleep,” he says. He unzips his pants, leans close to her ear, and says something.

“You’re filthy,” Annabelle’s mother says.

Annabelle thinks about filthy germs.

But her mother is laughing. “Not now,” she says. “Later—”

“Okay,” the man says. He reaches for his beer on the floor and knocks it over. “Hell,” he says. “Sorry about that.” He looks at Sam’s cage on the table, the plastic cover over it. He pulls the cover off.

“Where’s the bird?” he says.

Annabelle is being punished for letting Sam out of his cage. She is not allowed to watch TV for three days. She told her mother that she wanted Sam to be free. She didn’t tell her that he had bitten her finger, that she had unlatched the door and put her hand in to grab him, then run to the bathroom sink and turned the water all the way on and stuck him under the faucet. She felt his small body, his heart beating frantically in her hand.

“You’re bad,” she told him. “You’re bad and you have to be punished.”

He struggled and thrashed in the water, splashing her face and arms.

“I think you’re sorry now,” she said. “I think you’re sorry and don’t need to be punished anymore. And just remember, don’t try to fly away.”

But when she lifted him up he wouldn’t move. She patted him with a dry washcloth, but he stayed sodden and still. She wrapped him in the washcloth and rocked him back and forth. Finally she carried him outside in her pink Barbie purse and buried him around the side of the motel where she isn’t supposed to go, where there is nothing but a field of dead grass and an abandoned gas station where the high school kids leave empty beer cans and candy wrappers and cigarette butts.

Now Sam will be with her in hell, by the river where the goldfish will swim back and forth like tiny flickering pieces of fire. There is no way she will get the Holy Spirit now. She doesn’t care about not watching TV; she sits in her room, holding Simba, rocking him the way she did with Sam. Simba knows all about Grandpa, but he won’t help her.

In the afternoon she runs errands for her mother, brings her Diet Mountain Dew and Fritos from the apartment, and by the end of the day her mother has forgiven her.

The man is in room 220, just upstairs from them. No one ever stays here more than a night. They check in one day, and the next day they are gone, to someplace where there is more to see than some caves in the ground.

“You’re staying at Grandpa’s tonight,” her mother tells her.

When the night clerk, Jolie, shows up to relieve her mother, Annabelle has packed her pajamas and toothbrush and clean underwear and Simba and two Barbies in a plastic bag. Her Barbie purse is over her shoulder. In the purse is a tube of Cherry Chapstick, a pair of yellow sunglasses with daisies on them, some butterfly hair clips, and one blue feather that belonged to Sam.

On the drive over her mother talks nonstop about the man, whose name is Jim. Jim is a hoot. Jim likes to watch baseball and hockey. Jim sells office supplies right now but he could sell anything, anywhere, even something here in this town. Jim is a miracle from heaven, God has finally heard her prayers, and Annabelle should pray that he stays so she will no longer be a fatherless little girl.

Annabelle doesn’t want to pray. Jim isn’t her father; Joe was, but Joe has gone and she doesn’t know where. When he left, he forgot to say good-bye; she had watched his pickup turn out of the parking lot, and waited for him to remember and turn around, the way he often turned around because he had forgotten his glasses, or forgot he didn’t have any money to take her for an ice cream and had to go back and get some from her mother. Sometimes they would get as far as Denny’s before he remembered, and he would whip a U-turn in the middle of the road and then she would run in and get the glasses or money or his cigarettes, and run back to the truck. Maybe Joe will remember one day that he forgot Annabelle, and will come back for her in his truck that smells like cigarettes and air freshener, and they will go away and be married.

“I don’t want to go to Grandpa’s,” Annabelle says, as soon as her mother pulls out onto the road.

“Tough titties, baby,” her mother says. “Your old mother’s got a date.”

“He smokes cigars,” Annabelle says. “I think they have germs.” She tries to think of what else she can say, to get her mother to turn the car around.

“Those cigars are going to kill him for sure,” her mother says.

The trees go by on both sides of the road. They are tall, so tall it’s hard to see the top of them. Annabelle wishes she were a tree, with her feet planted firmly in the dirt behind the motel and her head sticking into heaven.

“I dance for him,” Annabelle says finally.

She wants to take it back as soon as she says it, because her mother’s face changes right away, and she pulls off abruptly into a gravel turnoff and jams on the brakes.

“What do you mean?” her mother says. “What do you mean, you dance for him?”

“Nothing,” Annabelle says, looking down into her lap.

Her mother has her by the shoulders. “You dance for him,” her mother repeats.

“Is it a sin?” Annabelle says.

She thinks about doing the hula in front of Grandpa, to the music she has to imagine in her head. She thinks about her arms moving from side to side, like waves in the ocean, wherever it is. She thinks of climbing into a boat that is too small for Grandpa and his wheelchair. A whale will tow her out to sea, a rope from the

boat looped around its tail.

“I do the hula,” she says.

“Oh,” her mother says, looking into her eyes.

But Annabelle feels, now, that her mother can’t see anything there, that she probably doesn’t want to see anything—not the fish, not Sam, and not Grandpa watching her dance, drinking his whiskey.

“Be careful,” her mother says.

“Yes, ma’am,” Annabelle says.

At Grandpa’s, Annabelle watches whatever Grandpa watches; tonight it is one of the crime shows he likes. There is a little girl about Annabelle’s age, but she isn’t really in the show, only her picture; she has disappeared, and the police are trying to find her, talking to different grownups and to the girl’s teenaged babysitter.

A commercial comes on, a big expensive car going fast down a highway toward some mountains in the distance.

“Fix me another drink,” Grandpa says.

He has been saying this for a while now, drinking fast. Annabelle hopes that means he is going to fall asleep soon. She goes and makes him another one. She sees the new box of chocolates in the refrigerator when she opens the freezer for ice.

“How about a little dance from my girl?” Grandpa says, when she brings him his whiskey.

“It’s my bedtime,” Annabelle says, which it is. She is already in her pajamas. She yawns, opening her mouth wide, stretching her arms up.

“Aw, c’mon,” Grandpa says. “Pretty please with Hershey’s syrup on top.”

“I don’t like chocolate anymore,” Annabelle says.

“Oh, sure you do,” Grandpa says. “You love it. My favorite little girl,” he says. “My little girl loves chocolate.”

“No, I don’t,” Annabelle says.

“You listen to your Grandpa,” he says. “Do what I tell you.”

“No.” She remembers her mother saying, Stubborn as a mule to the man in Sue’s Kitchen. “I hate chocolate,” she says. “And I hate dancing and I hate it when you wet your pants, so there.”

Grandpa looks at her a moment. Then he says, “You spoiled little brat.” He looks really upset. Annabelle has never seen him like this before. He has always been nice as pie, smiling at her, giving her treats and presents, asking her for dances. “Get over here right now.” He starts to rise from the couch, but sinks back down, wheezing and red in the face.

“I need my oxygen,” he says. His tank is in the bedroom. “Go bring it in here.”

“No,” Annabelle says.

“Now!” Grandpa says.

This is a Grandpa she has never seen, angry and needing his oxygen.

“I won’t,” Annabelle says.

“Oh, yes you will, Missy.”

He is breathing more slowly now, his face returning to its normal color. Again, he starts to get up from the couch. But before he is even off it, she has run out the door of the trailer and down the ramp.

“Get back here,” Grandpa calls.

But Grandpa is old, and slow. By the time he is at the door, she is running through the woods in the dark, branches stinging her face and arms.

When she can’t run anymore she stops, panting. She looks back toward the trailer, at a light pole on the road she knows is nearby. She can’t actually see the trailer, or Grandpa. Maybe he has gone back to get his tank from the bedroom, to sit on the couch and watch his show. Or maybe he is in the plastic chair in the dirt yard, smoking one of his cigars. The cigars will kill him one day. Her mother said so. Every day, Grandpa will get older and slower, and Annabelle will get bigger and stronger. If he chases her, Grandpa will wheeze and turn red in the face. The next time he asks for his oxygen, she will hide it, and he won’t be able to catch his breath. He will take in the air in little gasps, and then he will pass out for good, and be perfectly still. Then Annabelle will disappear, like the girl on the crime show. No one will be able to find out where she is. She will live in the woods in a fort, just her and Simba and the white cat Beautiful Lady of the Snow. Annabelle has never seen real snow, but she knows that somewhere, like at the North Pole, it falls all the time, covering the ground and trees and buildings, making everything it touches white, and pure again.

ONLY THE MOON

It’s Halloween, and I don’t have plans with anyone. No big thing. It’s only a Wednesday evening. From Sunday through Wednesday, if I happen to be alone in front of my old Sony TV with a succession of gin-and-tonics and a diminishing package of salt-and-vinegar potato chips, this is not a serious existential problem. After Wednesday, though, things get dicier. First there is Thursday, or “little Friday”: the bars and restaurants crowded, the clubs pulsing with music and bodies until the dawn hours. If little Friday arrives and I don’t have plans, a sharp but still-distant note of anxiety begins to sound—the harsh whistle of a train, coming from a long way off. On Friday it rumbles closer, and on Saturday night it appears from around the curve and bears down on me, huge and monstrous, threatening to cut me in two.

So, it’s only Wednesday. But Halloween complicates things: a day of bank tellers in bunny ears and fairy wings, the occasional drunken clown reeling from a bar at lunch hour with a smeared red smile, so that by evening the air is charged with the lonely ions of expectation. It is not a night to stay in, watching ill-trained teenaged actors get cut up with knives or crushed under electric garage doors or chased sobbing through the woods. I call three different friends, but everyone else has had the foresight to find a date, and no one invites me to tag along. Next I call Mona. Mona is way older, like sixty or so, and she hasn’t dated in years.

“Let’s go for drinks,” Mona says. “I was going to have dinner, but I’ll skip it. Nothing like a liquid diet.”

I can hear ice slithering around in a glass, and behind that her TV going. Predictably, someone is screaming. Nearly every channel has some kind of scare-a-thon happening.

“Drinks it is, then,” I say.

“I’ll just finish my drink,” Mona says, “and get ready.”

“Your pre-drink, you mean. Before we have drinks.”

“I get thirsty this time of day.”

“Always.”

All my friends are drinkers. Most Fridays we gather after work at some bar, then go to dinner and order carafe after carafe of house red. In my circle, the parties last long—until the revelers slip to the floor or stagger off to pass out on a neighbor’s lawn, maybe climbing into their cars, if they have them, to wend their erratic way home through the deserted streets. We start the weekend mornings with a Bloody Mary or Mimosa or Ramos Fizz, with Walprofen and Aleve and Excedrin, with groans and nausea that gradually slide into hilarity. We get through our McJobs with flasks, and have beer with lunch. We head out of Starbucks and Kinko’s and financial district offices for fifteen-minute cocktail binges on our scheduled breaks. Forget AA. AA is for losers who can’t handle their shit.

“Let’s go to the Redwood Room at the Clift,” Mona says. “I haven’t seen it since it’s been renovated.”

On her TV, a girl’s voice goes, Oh, God, no. Oh, God, please, no, no.

“Pick you up in an hour,” I say.

“I’ll treat, of course. But make it sooner. I don’t want any fucking little kids at my door.”

Mona always treats me. She has that appealing combination of wealth and carelessness with money. Hundred-dollar bills spill from her Italian leather wallet. She’s big on cashmere coats; she owns five. Gucci and Fendi bags, Ferragamo shoes, Dior scarves—Mona always looks like she stepped out of a photo shoot, materializing into the air on a breath of floral perfume from a fashion magazine. Her hair is white-blonde, sleek and smooth as metal, and falls straight to her shoulders. Her eyes are a color of blue that looks like it has metal in it, too. Mona exudes an aura of ease and luxury, of eternal impossible beautiful moments in exotic locations where even the inanimate objects, like chaise lounges and sea walls, admire your flawlessness.

In honor of Halloween I put on a long leopard-print skirt with slits on each side up to mid-thigh, and a black velvet bustier with leather laces. For good measure I wear my black hat with the square of lace hanging down the back and the fake roses on the brim, and slather on the makeup. I drink a quick toast before I leave, a cold shot of Estonian vodka raised to dodging the bullet of sitting at home in my bathrobe, in thrall to scenes of a couple being terrorized by a doll in overalls. I’ve been transformed into a sexy twenty-seven-year-old jungle cat out on the prowl, ready for whatever magic the night may bring. When I get in my car, a guy in a George Bush mask whistles, and his friend, encased in an alien creature with eyes the size of tennis balls, meows at me.

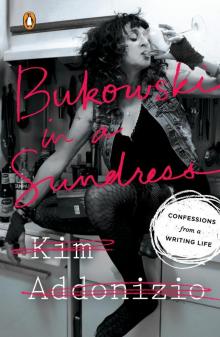

Bukowski in a Sundress

Bukowski in a Sundress Now We're Getting Somewhere

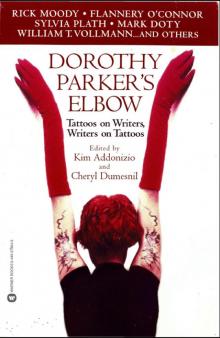

Now We're Getting Somewhere Dorothy Parker's Elbow

Dorothy Parker's Elbow